There were two main sets of interim deliverables that we assigned to ourselves to complete fairly early on:

- detailed methodology development and planning (after we had read all the literature, etc. ) and

- data standards that would enable us to use the same tools and talk the same lingo.

This update discusses data standards (and our lack thereof). Our task was to find a common way for Fast-Trips to be able to interact with our three model systems: SF-CHAMP (SFCTA), SoundCast (PSRC) and Travel Model One (MTC).

Standards everywhere you look

First, let’s talk about the standards that we already have, use, or will use as a part of this project at PSRC, MTC and SFCTA:

- OMX for skim matrices and aggregate demand files (i.e. visitor travel)

- Cube Networks:

- .NET highway, bike, and pedestrian network files

- .lin and .link transit network and service files

- .access, .zac, .xfer, and .pnr SF-CHAMP network wrangler files

- EMME data bank

- APC data dumps

- GTFS schedule based transit service

- HDF5 disaggregate demand files

Clearly that is a lot to consider and we were hesitant to add even more standards to the mix.

We could have opted to code a lot of flexibility into Fast-Trips itself and have it accept

a wide variety of inputs, or we could standardize the input that it was expecting and use

outside forces to commandeer the variety of data we needed into that standard. We chose the

latter approach, not just because of the sheer variety of formats, but also the variety in how those formats are

used at each agency. For example, while MTC and SFCTA both use Cube, the data that

they include within their Cube networks varies, and some common data elements use different units as well.

Where a Fast-Trips data standard fits in

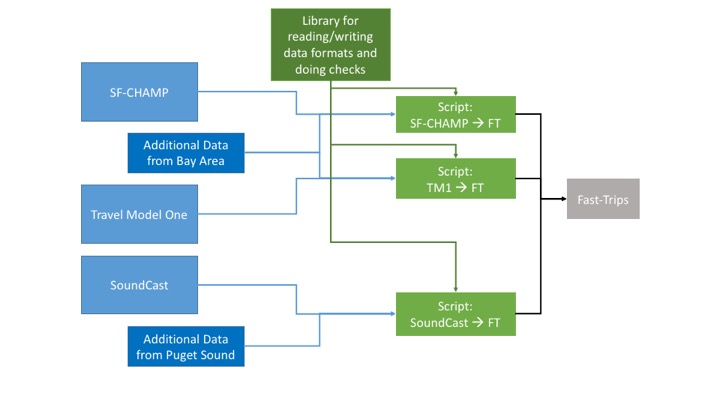

Our chosen approach for dealing with the varying input data is shown in the figure below.

The blue items on the left represent the unique standards and uses for each individual agency

along with the variety of data that might be available in each region. The green boxes in

the middle represent the “glue code” that Tasks 2 and 3 (Networks and Demand) are responsible

for developing alongside Task 8 (Implementation). The scripts that glue the individual model

data to the Fast-Trips standard will make use of a shared library that has a standard set of

writing methods and checks. The grey box, represents the network and demand standard that

Fast-Trips will be reading in. The read methods for Fast-Trips will be developed as a part

of Task 6 (Software Development). The next step was to agree upon the format that the scripts

would write and that Fast-Trips would read so that they would be aligned with each other.

Design Development

There were a multitude of considerations that went into developing the Fast-Trips data standard:

- use as much inertia from existing standards (e.g., GTFS) as possible

- define such that you don’t break functionality for existing tools

- separate out minimum requirements from optional information

- don’t store duplicate information

- flexibility for various approaches w/out unneeded dispersion

- each agency can fill in gaps better than Fast-Trips

- make coding errors obvious and easily fixable

- limit the necessity of additional tools/libraries

Use inertia: start with another standard

The first thing we did, was evaluate existing standards. This exercise was most relevant on the network side where there were already two slightly different standards between GTFS and the existing Fast-Trips input format, which was not backwards compatible with GTFS. Given the multitude of tools and code written surrounding GTFS, we decided to start with its standard, and make everything that was mandatory in GTFS mandatory in our Fast-Trips standard, even if it wasn’t needed to run Fast-Trips (extraneous mandatory elements do not need to be good data in every implementation… they just needed to be there so the code can run). Starting with GTFS meant that, as our first major decision, we had adopted a CSV-based format with a header line containing case-sensitive variable names.

Don’t break backward compatible functionality

While GTFS contains a bunch of data, it doesn’t have everything we needed. However, adding

columns to the GTFS files would most likely break the ability of existing GTFS tools to read

them. Therefore, we adopted an addendum to each GTFS file that contained the additional

information and an identifier column that could link between them. One example is

stops.txt

(a standard GTFS file) and stops_ft.txt (our code extension) which contains a variable

stop_id that links the

additional information we will need for Fast-Trips (e.g., shelter, lighting, bike parking,

etc.) from stops_ft.txt back to stops.txt.

Define minimum requirements and optional information

It is possible that some very ambitious transit agency does have information about every escalator, vehicle, and bench

on your network and the age, income level, and trip purpose of every trip in their model…

but let’s not design a standard that requires it! We were very explicit in our standard to

say what was required by Fast-Trips versus what each agency could choose to include for their

specific implementation. For example, while travel data that comes from the activity-based

simulation contains the ages, incomes, and value of times for each passenger, that is not

often the case with what we call “auxiliary demand” (such as visitor trips and through trips)

where we often only estimate the origin, destination, time of day, and mode. Therefore, the

demand data only requires the minimum information in trips.txt and makes the attributes in

person.txt and household.txt

optional, rather than requiring them to be filled with placeholder information.

Don’t store duplicate information

Duplicating information within a standard could lead to conflicting information with no clear path about which version is correct. Therefore, the only information that should be duplicated between or within a file should be for the purposes of identification and linking between files.

For example, the decision to separate out person and household level data in the demand files meant that we didn’t have to repeat the same information about the household for each person that lived there. In addition to preventing conflicts, there is the added benefit of saving storage space.

Have flexibility for various approaches

The whole point of having standard is to come up with a set of expectations about the information that will be provided. However, even between our three agencies, we often had three different methods for dealing with things. One example is the selection of park and ride lots, where we had a spectrum of choosing it on the demand or network side:

- Travel Model One allows the network model to choose any park and ride lot within a specified distance

- SF-CHAMP pre-picks a set number of “likely” park and ride lots and lets the network model pick between those

- SoundCast has the demand model pick the park and ride lot and give it to the network model

We had many great philosophical discussions as a group about what was the “right” approach in this case, but at the end of the day we wanted Fast-Trips to be able to accommodate any of them.

In the trips.txt file, there is an optional field PNR which contains a list of nodes.

If there is only one node in the list (i.e. with SoundCast), then the drive access link will be

forced through that node. If there are several nodes in the list (i.e. with SF-CHAMP), then separate drive

access links will be available going to each Park and Ride lot, and the network model will

choose the best one. If there is nothing specified (i.e. with Travel Model One), it is a

free-for-all and the network model will select the one it believes to be the best.

Limit unnecessary dispersion

While we agreed that we wanted to accommodate a variety of methodological approaches and

specifications, that doesn’t mean that we can’t coalesce around a singular vocabulary when

we “mean the same thing.” For example, mode names can be standardized. Instead of each agency

using a different label for light rail (e.g., LRT, Light-Rail, and Light_Rail), our standard

suggests (but does not require) that you use Light_Rail.

Agencies decide how to fill in gaps in required data - not Fast-Trips

Sometimes the data we have doesn’t quite meet the required minimums. In these cases, some assumptions will have to be made. Rather than having those assumptions decided a priori within Fast-Trips, we decided to let each agency decide their own best way for creating that minimum required information.

For example, there are two pieces of information within the demand standard that SF-CHAMP

does not have enough information to provide: (1) departure minute (SF-CHAMP uses lumpy time

periods), and (2) whether the origin or the destination is the more important time target.

In the previous version of Fast-Trips, the time rigidness was decided by a field called direction,

which specified which tour-half that particular trip was on. Outbound direction meant

that arrival times of the trips were more important and vice-versa. The proposed format

keeps both arrival and departure times from the ABM and has an additional column called time_target

to let Fast-Trips know which time to give more importance to during path choice.

The intent with the explicit specification of time_target is to allow the ABM to make

the decision about whether the departure or arrival time is more important and to give

that information to Fast-Trips, rather than having the rule within Fast-Trips itself.

Make coding errors obvious and easily fixable

Using number-string lookups for common words like modes, vehicle types, and trip purposes

would save a small amount of space and input read time. However, if I open a file and see

"1, 88" I am much less likely catch an error compared to "commute, pogo stick".

Limit necessity of additional tools/libraries

Sure HDF5 is quicker and smaller and SQLITE is alluring, but if we didn’t already all have it installed on our machines for “something else” we eliminated it from contention.

The hardest part?

Fares were by far the most difficult aspect to think through. There are just so many policies

and possibilities. While we tried really hard not to contradict anything that already existed

in GTFS, it just wasn’t possible. In this case, we created the table fare_attribute_ft.txt

which is a complete substitute for the GTFS table fare_attributes.txt

and therefore does not link back up with it.

In the existing GTFS specification, the one-to-one relationship between route_id and fare_id

in fare_rules.txt

precludes the ability to represent fares that vary by time of day for

the same route, e.g. peak/off-peak. Our work around is to use fare_id, start_time

and end_time in fare_rules_ft.txt to return fare_class, which is then used in

fare_attributes_ft.txt to return the correct fare.

The only difference between fare_attributes_ft.txt and the standard GTFS fare_attributes.txt

is that fare_class is used instead of fare_id. Most GTFS feeds to not include data on

fare at all, which is why this feature was likely overlooked. However, it may be worth

suggesting to the GTFS team as a suggested modification.

The Standards Themselves

The standards themselves can be found in the appendices to the Network Design and Demand Design documents. As these are “working standards” and are subject to change as we go through the project, we will be version controlling them as we make changes.

Other Thoughts and Questions

There is definitely a temptation to shift away from a GTFS-based format given its complexity. However, at the end of the day the sheer inertia from its widespread adoption won out. Some other things that we have been thinking about regarding data standards that we would love some feedback on:

- What is the best way to version control data standards? We have seen some examples on the open knowledge foundation of using MarkDown files stored on GitHub

- Where is the best place to store and version control data? There are lots of great options now such as datahub.io / CKAN, and GitHub’s LFS, but the tech behind it is a subject of ongoing research. There are also storage and management solutions such as Socrata and FigShare which have fewer features to track line by line differences, but are more customer-facing.

- For now, we have just decided on a standard for the data itself and ignored meta-data (bad modelers!). There are numerous emerging data-package standards that enforce meta-data…but which to use? Google’s Dataset publishing language uses XML, and OpenKnowledge’s uses JSON.

Next Up

We will be evaluating how well these standards do over the course of the project. They will likely change based on:

- decisions we make down the road;

- feedback from the community;

- usability (or lack thereof); and

- changes or appearances of other standards.