A question we understandably get a lot is what is so different about Fast-Trips compared to what you do now? The generic answer [ for most model development projects] is that it helps us answer important questions relevant to planners and decision-makers that we can’t answer now. Realizing that the lack of specificity in this response leaves a little to be desired, we thought we would dedicate a post to diving a little deeper:

- what are the specific features that differentiate it from the conventional process?

- what questions will in answer?

Promising Characteristics of Fast-Trips

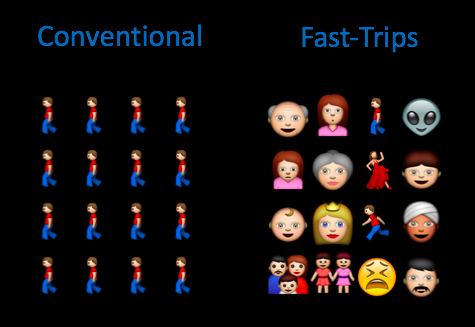

1 - Heterogeneity of riders.

What does that really mean?

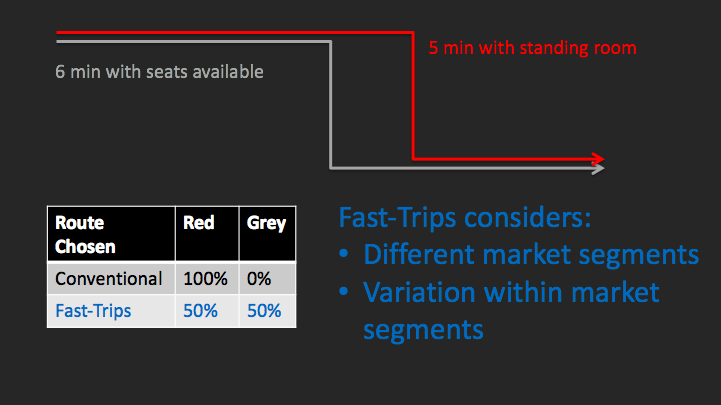

Fast-Trips uses simulation, which enables it to consider the spectrum of unique combinations of why riders might choose one route over another. It has the ability to know that some riders might prefer shorter walking distances and seats while others will prefer the fastest possible route.

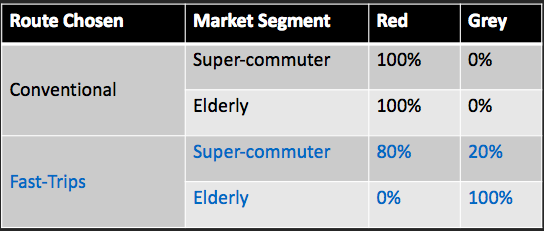

Furthermore, rather than grouping every individual into a category (“market segment”) that chooses based on the average desire of the people in that category (i.e. all the speed-demons will pick the 38L despite there not being any seats), Fast-Trips has the ability to understand that “speedy” is relative - and that some speed-demons are more speed-driven than others (i.e. some might be okay with a trip that is a minute slower, but where you can get a seat to read your book.

Conversely, different types of riders affect the transit system in different ways. Some are slow to board, some use cash versus a fare-card which makes the bus stop for longer, some may need a spot for their wheelchair. All of these things affect the performance of the transit line.

How is that different?

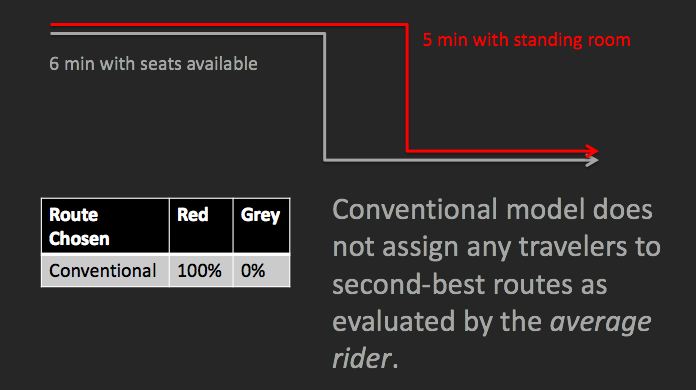

Conventional transit path building methods use a singular set of optimization parameters for all transit riders. The problem with this method is that it results in an all-or-nothing assignment of everybody going between that general origin-destination pair to a singular transit route.

Why do we care?

More consistent with reality: It is what happens in real life; therefore you will get more realistic sensitivities and results.

Realistic sensitivities and results: Aside from the simplification of theory, this can be a significant problem in practice because transit routes that are slightly different from each other can have vastly different levels of attractiveness to riders.

If you want to design a system that works for everybody - you can’t assume everybody will be well-served by a system optimized for the “average” citizen.

2 - Detailed representation of individual people and vehicles over time

What does that really mean?

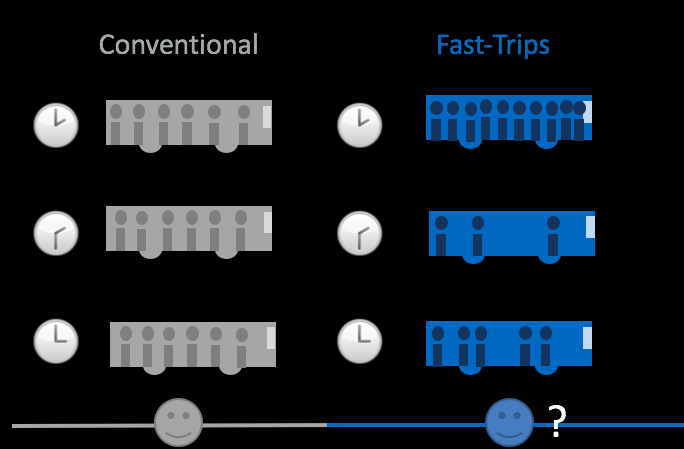

Fast-trips tracks individual transit vehicles and people as they move through space and time. The overflowing 38L bus that arrives at Masonic Blvd. at 8:32 AM is represented separately from the bus that arrives at 8:35 AM and has free seats.

Similarly, Fast-Trips can show that individual riders may have different experiences on the same vehicle. If you are the person who got a seat, you will feel very differently about your trip than the person who got passed-up or is squished near the door.

How is that different?

Conventional transit path building models use aggregations of time periods, vehicles, and riders.

This means that they cannot capture variations in experiences across vehicles or riders which makes

it difficult or impossible to calculate variables such as reliability or capture issues such

as pass-ups or crowding.

Furthermore, because conventional transit models do not have a concept of an individual rider, you cannot easily summarize a rider’s experience across the entire system (critical for capturing reliability from the rider’s perspective) or calculate “select links.”

Why do we care?

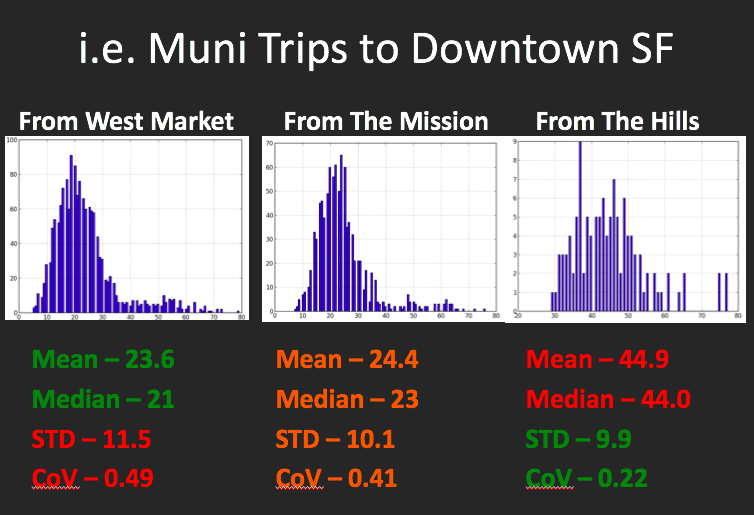

Capture important phenomena: such as crowding, reliability, and the scheduling of infrequent transit lines. Since Fast-Trips models individual riders, you can observe the distribution of experiences rather than the average experience.

Infinite summary options: including select links, tracking individual people or vehicles, and analyzing how specific groups of people or vehicles perform. This includes the ability to analyze reliability from the rider and vehicle perspective.