What is a hyperpath, anyway?

Over the past few months, our team has spent a lot of time exploring the methods in the existing Fast-Trips software. The more we run the software with various examples, the more questions we had about how exactly the algorithm works as written in code (which is slightly different from published papers), so we thought we would document what the algorithm actually does in this blog post.

Let’s start with the literature.

Nguyen, S., S. Pallottino, and M. Gendreau, 1998

For any given destination, a strategy specifies a set of attractive lines for every stop and an alighting stop for every line that may be boarded when traveling toward that destination, and a hyperpathis the unique acyclic support graph of a strategy.” ( )

Khani, A., M. Hickman, and H. Noh, 2015

A hyperpath, as defined by Nguyen and Pallottino 1988, is an acyclic subnetwork with at least one link connecting the origin to the destination, and where at each node, there are probabilities for choosing the alternative links.”

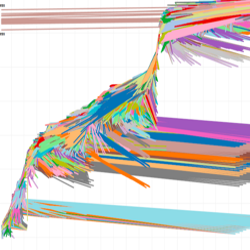

I still find this a bit confusing, so let’s start with a visualization (based on Figure 5 from Khani et al 2015):

Some Definitions

In this graph, a preferred arrival time, or PAT, is an input to the algorithm. dt is an input parameter, specifying the maximum time window for which outgoing links from a single stop are considered a hyperlink. Hyperlinks consist of a set of links from a single origin to multiple possible destinations. In this example, two transit vehicles travel from stop1 to stop5 within the time window, and they travel at the same speed, while another vehicle travels from stop1 to stop3. Similarly, two vehicles travel from stop4 to stop5, and one vehicle travels from stop2 to stop3. Stop5 is close enough to the destination to walk, and stop1 and stop2 are both walkable from the origin. In total, this hyperpath contains five feasible paths between the origin and destination, but only three separate hyperlinks.

When a preferred departure time (PDT) is specified rather than a preferred arrival time, the graph elements (and algorithm described below) are reversed. That is, hyperlinks consist of a set of links from multiple origins to a single destination. For the remainder of this post, we will discuss outbound trips with a preferred arrival time.

Algorithm

The original SHRP2-C10 version of FAST-TrIPs as well as the version of Fast-Trips currently under development by our team currently both use the following algorithm to formulate a hyperpath given a preferred arrival time, PAT and time window, dt. The algorithm is a variant of Dijkstra’s Algorithm for finding a shortest path, except it’s constructing a hyperpath in order to find a set of paths with probabilities associated with them. The stop label represents our best guess of the overall generalized cost ( or impedance ) of travelling from that stop to the destination, and it’s formulated as the following logsum (from (2)):

where

- li is the label for stop i

- θ is the dispersion parameter used for modeling stochasticity. This parameter is between 0 and 1. Higher values for the parameter mean that higher cost links within a hyperlink are devalued compared to the lowest cost links in the hyperlink. That is, if the lowest cost for a hyperlink is c, when a new link gets added to the hyperlink with a cost higher than c, when θ is closer to 1, the more the new link has a low probability compared to the lowest cost link. The higher θ emphasizes the lowest cost link more.

- Pa is the set of available links (transit vehicle trips or transfers from stop i)

- cpi is the cost to reach the destination from stop i using link p. This cost is the label of the next stop (call it stop j) plus the link cost from stop i to stop j, so cpi = lj + link_costp

[ We will discuss the effects of these parameters and how to judge them in a separate post. ]

A stop state is the combination of a stop label (l) plus the list of links (transit trips, transfers, and access or egress links, Pa) from that stop to other stops (e.g. the links to the right of each of the stops in the figure above). In our example, we have a preferred arrival time at a destination, so the algorithm sets labels and stop states backwards from the destination:

- Initialize stop states. For each transit stop with an egress (e.g. walk) to the destination, label that stop. Assume these walk links are as late as possible in time (so arrive at PAT) so that we have the the maximum number of options for getting to that transit stop; since the exact time of these walk links aren’t clear, they are represented as thick green bars in the above diagram. The label at these stops is just the link cost, which in this case is typically based on the egress link travel time, and the stop state consists of just that egress link. Add each stop and its label to a label stop queue.

- Loop to label stops. While there are stops in the label stop queue:

- Remove the stop i with the lowest label from the label stop queue.

- Update the stop states for transfers to stop i. That is, for all the transfer links from another stop j to stop i, update the stop state and stop label for that stop j so the hyperpath includes the possibility of transferring from stop j to stop i. So in the same way we treated the egress link times during stop initialization, we start with the assumption that these walk transfers are as late as possible in time (e.g. in time for the latest departure from stop i as determined by the stop state for stop i). Add stop j and its label to the label stop queue.

- Update the stop states for trips to stop i. That is, for all the transit vehicle links from another stop j to stop i, update the stop state and stop label for stop j so the hyperpath includes the possibility of taking that transit vehicle from stop j to stop i. The trips are restricted to those which arrive in time to catch the latest departure in from stop i as determined by the stop state for stop i. Add stop j and its label to the label stop queue.

- Finalize origin state. After all the stop labels have been removed from the label stop queue, we need to initialize a stop state for the origin point by iterating through the access links and calculating a cost based on the labels of the reachable stop i combined with the cost of the access link. Assume walk access link to stop i is right before the earliest departure from stop i so that none of the links out of i are excluded.

- Enumerate paths. In theory, the origin state now has a label that has a cost that encapsulates the costs of all the trip links and transfers. However, recall all of our assumptions about the timing of walk links (egress, transfer and access). These result in inaccurate assumptions about wait times which can only be determined when actual paths are enumerated. We therefore walk the labeled hyperpath and generate all of the actual, realizable paths from it. At this point, we can fix the timing of the walk links and therefore have actual wait times. The path costs here are used to calculate the probability of each of these paths.

Issues

Now that we know how FAST-TrIPs defines and creates a hyperpath, a few issues arise that we are grappling with.

Label Stop Queue Order

In Dijkstra’s algorithm, nodes also get removed from the priority queue based on having the lowest label ( least cost ). The proof of correctness for Dijkstra’s algorithm is based in the fact that label[v] = label[u] + link_cost[u,v]. However, for the Fast-Trips algorithm above, this is not true, and so the stops that get pulled off the label stop queue do not necessarily have final labels. Fast-Trips labels can be updated at a later point, and the fast-trips algorithm does not then account for the subsequent updating of stop states for trips and transfers to that stop after that label update.

Link-Additive Costs

Before enumeration, hyperpath costs must necessarily be link-additive, and even then, the cost is not accurate until enumeration because of the uncertainty with the walk links. This could cause problems with costs that are not link-additive, such as fares which can have complicated transfer rules. For example, one could take a bus to rail to bus trip, and the second bus trip would be a free transfer. When the path is enumerated, this would be easy to account for, but during the hyperpath generation, the links further down the hyperpath are uncertain.

There is a risk is that we may not generate a reasonable path in the labeling stage, and then it can’t be corrected in the enumeration stage. So why not generate all feasible paths in labeling? For one, it would take forever, but also we don’t think it is possible to know if we didn’t generate all the feasible paths. We welcome others comments on this topic, as it is one that we have been thinking about.

Path Overlap

When evaluating the value of a transit path, we typically take into account other path options to determine the value of that option. That is, if two paths exist that are virtually the same except but with a small difference – for example, if a destination is between two stops, two options could be the same except for getting off the same transit vehicle at one stop or the other – then the value of those paths together should not be much greater than the value of one of those paths individually. This affects probabilities as well; if there is a third option that is much different but as good as the other two, then the probability should be around 50% for the third option and 50% for the other two. Therefore, accounting for path overlap needs to be included in both path evaluation and in calculating any overall “quality of transit” metrics.

References

- Nguyen, S., S. Pallottino, and M. Gendreau. Implicit Enumeration of Hyperpaths in a Logit Model for Transit Network. Transportation Science, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1998, pp. 54-64.

- Khani, A., M. Hickman, and H. Noh. Trip-Based Path Algorithms Using the Transit Network Hierarchy. Networks and Spatial Economics, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2015, pp. 635-653.

- Noh, H., M. Hickman, and A. Khani, 2012, Hyperpath in Network Based on Transit Schedules, Transportation Research Record, Vol. 2284, PP 29-39.

![Hyperpath Example [ click to enlarge]](/img/posts/hyperpath-example.png)